[ad_1]

India’s booming economy is the envy of other major markets. But beyond the hype and expectation, people who watch the country closely are flagging warning signs.

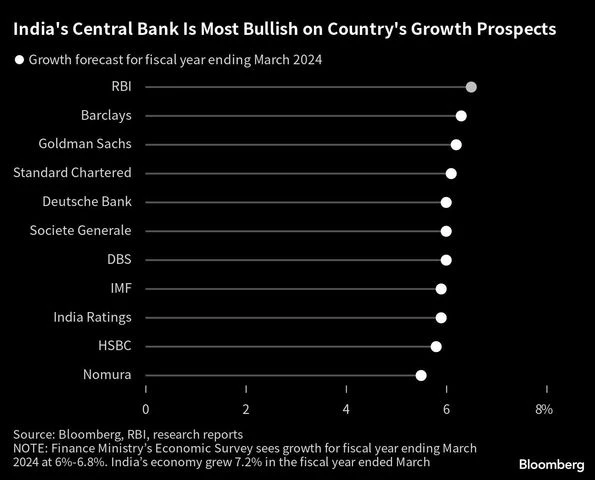

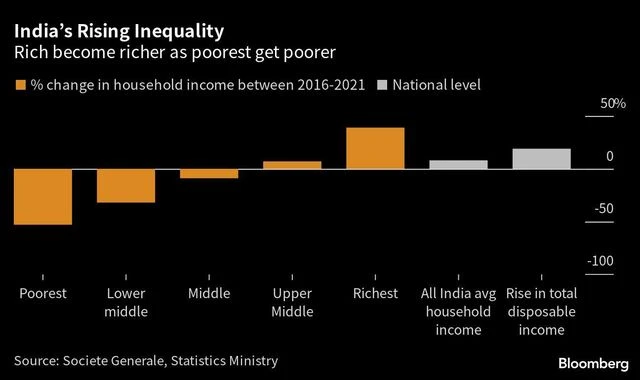

The nation is heading for a slowdown, analysts who cover it say, as rising inequality squeezes consumer spending among the poor — and the hundreds of millions in the middle class. The pessimism comes even after the latest growth figures blew past estimates last week, rounding off an expansion of more than 7% for the fiscal year.

Any cooling — especially one driven by inequality — would pose a challenge for Prime Minister Narendra Modi as he seeks a third term in general elections next year. It would also increase the chances the central bank, which decides on monetary policy this week, will cut interest rates earlier than expected.

India grew by 6.1% in the three months ended March compared to a year earlier, well beyond the 5% estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg, driven mainly by increases in services exports and government spending. It expanded 7.2% for the fiscal year through March, continuing a post-pandemic recovery that outstrips major peers.

)

SocGen and others say consumer demand will decline as the nation’s rich get richer but others struggle with the cost of living. That’s creating what’s known as a K-shaped recovery in consumption, where luxury items sell well but basic goods go in the opposite direction, Kundu said.

“Saving is difficult when living costs themselves are this high,” she said. “I will wait until December.”

)

Private consumption fell 3.2% in the three months ended March from the previous quarter. This may be due to reduced spending by the urban middle class, which should come as a concern for the country’s growth, said Rupa Rege Nitsure, chief economist at L&T Finance, the commercial and personal finance arm of India’s largest construction company.

“It’s not a broad-based recovery,” she said, adding this means it will be difficult to sustain.

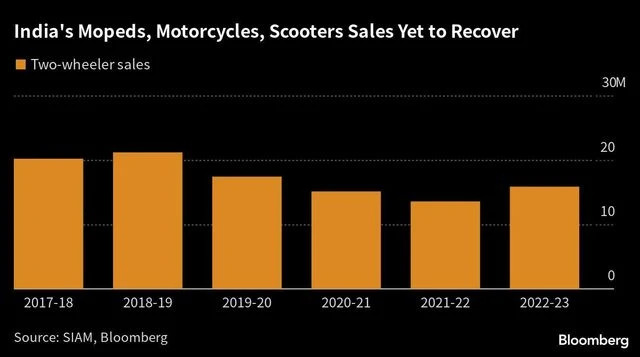

Two-wheeler vehicle sales, a key gauge of rural demand, remain below their pre-Covid levels.

)

One implication of a slowdown is likely to be on interest rates.

Another impact, at the margins, may be on Modi’s prospects in the 2024 polls. India needs growth of 8% to 8.5% annually to employ the 90 million new nonfarm workers that will join the workforce by 2030, a McKinsey report in 2020 said.

Even with the expected slowdown, India will still be the fastest-growing major economy in the world this year, according to International Monetary Fund projections. Germany is in recession, some observers expect the US to follow, and the IMF projects China will grow 5.2% in 2023.

And even if India slows in the short term, analysts remain bullish on its long-term prospects. “India is rising in the world order,” Morgan Stanley equity strategist Ridham Desai and colleagues wrote in a report on the country’s markets this month.

Mishra’s wages have hardly changed since the before the pandemic even as inflation surged. He earns about 12,000 rupees ($145) a month. These days, he sends less money home to his family in a village in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. And they, in turn, spend less.

“There’s no point arguing on salary,” he said. “Somebody else is always ready to work for a thousand rupees less.”

[ad_2]

Source link